Guest Contribution by Nick Trickett

My Kingdom for a Railcar

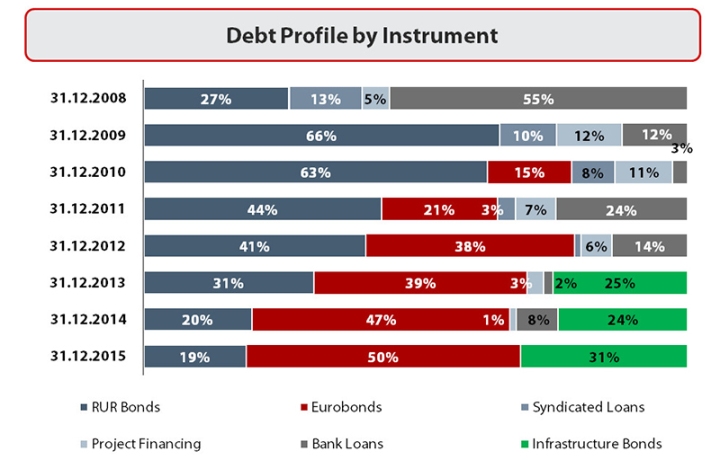

Recently retired SVR intelligence chief Mikhail Fradkov—targeted by US sanctions—was to be named head of Russian Railways according to reports from Vedomosti. The Kremlin backed off of replacing current head Oleg Belozerov—not targeted by sanctions—for fear of repercussions among investors holding the company’s Eurobonds. If investors get antsy and demand early repayments, the company could default. Nearly half its debt is held in Eurobonds.

Russian Railways—a 100% state-owned monopoly—employs over a million people, ships as much as 60% of the country’s cargo, and accounts for roughly 1.5% of Russia’s GDP. The company’s size, poor performance, politicization, and social role put the Kremlin in a bind if it wants to make changes, real or cosmetic. The Kremlin’s reticence to name Fradkov head reveals fear of a default rippling out into the economy.

Railroad to Ruin

Since 2008, Russian Railways has seen a 22% increase in its freight turnover and has held steady since the Ukrainian Crisis began despite huge declines nationally in imports and container traffic. In that time, profit margins have shrunk to the point that the company’s current balance sheet shows that after losses the last two years, this year’s income is largely comprised of subsidies. The company has seized greater market share through a combination of uneconomical discounts on goods or routes meant to lure business from trucking firms, rising gasoline costs from increased fuel excise taxes, and new Federal taxes on truckers’ use of Federal roads.

Sustained “growth” is as much a result of oligarchs’ maneuvering as positive economic indicators. Iron, petrochemicals, machines and machinery equipment—some of the most profitable freight—only accounted for 13% of freight in 2014 and that’s likely worse now. Coal, mining exports, and agricultural products have shown the most life since 2014 and represent a larger share of production and exports. The railways are shipping more, making less, and relying on growth in sectors that are relatively unprofitable in terms of tariffs. Reforms are desperately needed but very unlikely in the current political and economic climate. It remains to be seen if the proposed 25% privatization of the railways over the next three years meaningfully corresponds to reform.

Life and Debt

The railways have little to spend. In the last four years, the railways’ capital investments—those not supported by the state—have dropped four-fold factoring in currency devaluation. State funding has had to make up the difference. There was a large expansion of the firm’s debt in 2013 to pay for a modernization program for the Trans-Siberian Railroad and the Baikal-Amur (BAM) line. The BAM investments are aimed at mining projects and transport capacity that do not provide great return for the company.

Of its post-crisis investments, the most notable is a rail-line from the Southern Russian city of Krasnodar that circumvents Eastern Ukraine and improves rail transport for goods in and outbound from Crimea. Though the project provides some economic benefits, it’s largely political in nature and will benefit agricultural freight most. The company won’t make much off of tariffs.

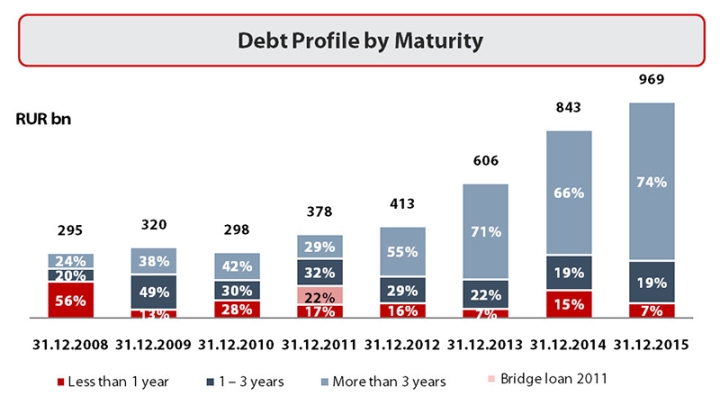

Without strong profits, the company can only carry out the ambitious infrastructure investments the economy needs by taking on debt. Here’s a snapshot of its debt growth from the company’s website:

Until early October, the company had not issued any new Eurobond debt since March of 2014. Both were semi-annual, meaning that RR has to pay out to investors twice a year. One was valued at 15 billion rubles with a 9.2% coupon rate—the rate at which RR has to pay back investors relative to its value. The other was valued at $500 million with a rate of 3.45%. Without that capital, the company can’t meet its obligations. Clearly, a change in strategy or leadership is necessary to improve profits. By all appearances, Fradkov was a logical candidate for the job.

Why Fradkov?

Fradkov’s resume includes time as Deputy Minister of Foreign Economic Relations, Deputy Secretary of the Russian Security Council, Prime Minister, and head of the foreign intelligence agency (SVR). Those who know him praise his intellect, brilliant command of English, and technocratic savvy. Despite his role in Russia’s intelligence community, Fradkov is not a silovik from the security establishment. Free marketer Anatoly Chubais has praised his economic acumen, as Fradkov has worked on trade and economic security issues throughout his career. The appointment was in fitting with the ongoing shuffle of Kremlin leadership in search of technocrats. Any panic among investors could sink the company and cause a real social and political disruption for the Kremlin. The sanctions placed on him are a tremendous political liability for a firm without the leverage that oil or gas afford.

A Worst-Case Scenario

Russian Railways’ size is an Achilles heel for the regime. Railway employees are taken care of, evidenced by the fact that the company’s employees earn as much as 31% more than the national average for their work. When times are tough, Russian firms cut wages or hours instead of jobs to preserve social order. Since the company employs over a million people, a run on debt could trigger a late wage or wage-cutting crisis requiring a large bailout. Labor strikes are already on the rise around the country but remain regionally isolated. The Kremlin is watching carefully. Railways can nationalize a regional or local problem.

Renewed maneuvering in the EU and US over sanctions in response to Russia’s actions in Aleppo and Ukraine has yet to produce agreement on action. There is no unified position among EU states and the US about what to do next. More talk may be enough to spur investors to demand early repayments if it picks up steam. The Kremlin would have to pick up the tab.

Nick Trickett currently works as a policy analyst on the Eurasian space at the Foreign Policy Initiative in Washington D.C. and is a contributor for Global Risk Insights. He has focused and written on Post-Soviet foreign policy and energy politics, with an emphasis on Russia’s Pivot to Asia, Russia’s East Asian energy relations, and evolving projects in the Eurasian space such as the Silk Road or the North-South Transport Corridor. He is finishing an M.A. in Eurasian studies through the European University at St. Petersburg.